Hi everyone! This is about that Beckett quote. Thanks to Sarah Black, Lucy Schiller, Gillian Hemme, André Callot, and Jess Barbagallo for helping me figure this out.

I tried to put it in the dumbest fucking font possible on Google Docs. Look at how stupid that looks. It looks like the writing on the wall of a children’s boutique in Bucktown, Chicago. It looks like the writing on the wall.

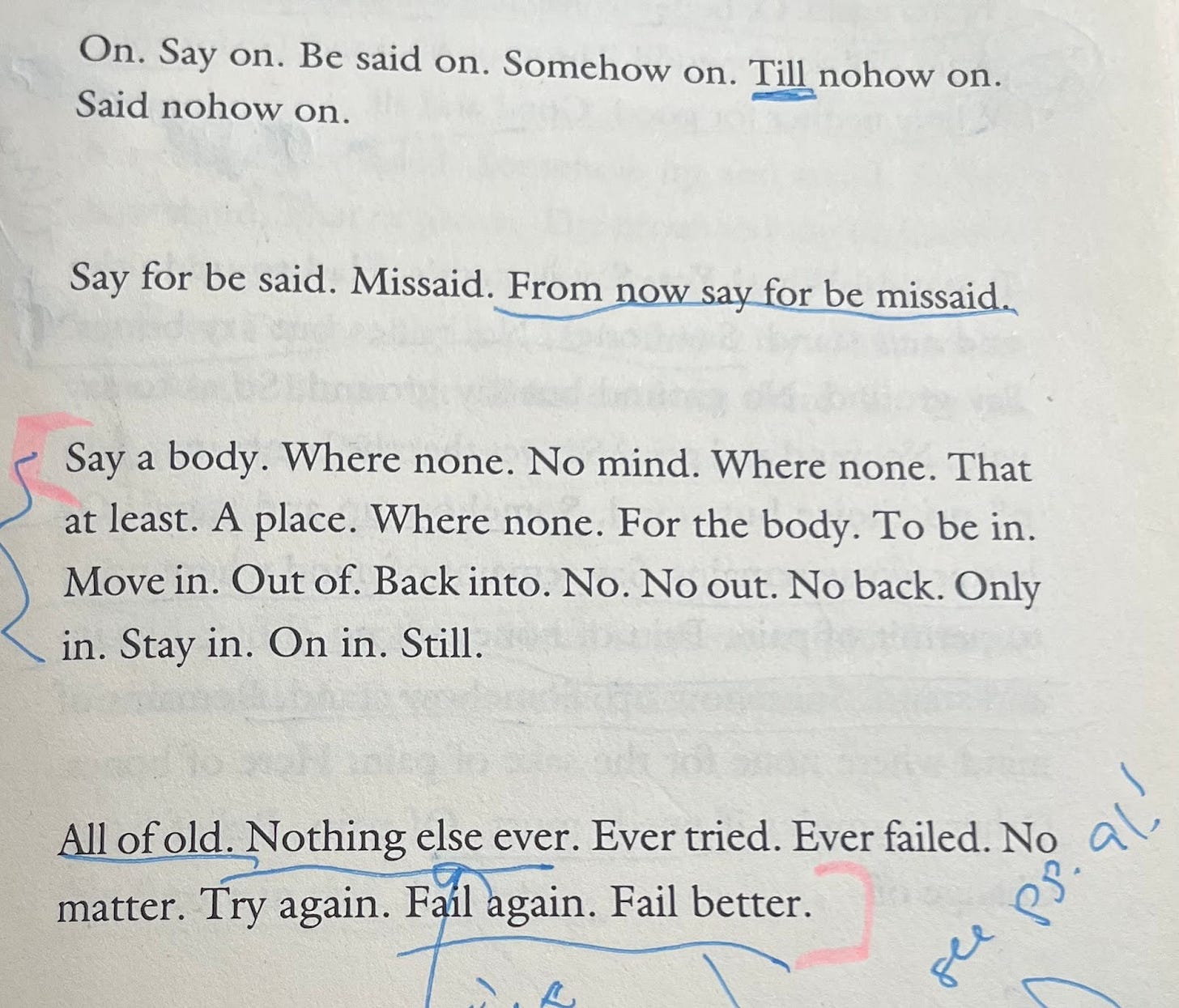

First of all, it’s not even from one of his plays. It’s not from one of his novels, either. It’s from a prose piece. The prose piece is called Worstward, Ho! It was written in 1983, and published in 1989. It’s experimental fiction. Beckett had a life-long obsession with both language’s capacity to evoke as well as its inevitable failure to fully evoke whatever it is it’s trying to say. I share this obsession, but of course I’m not nearly so good at writing about it.

Here:

But wait! There’s more!

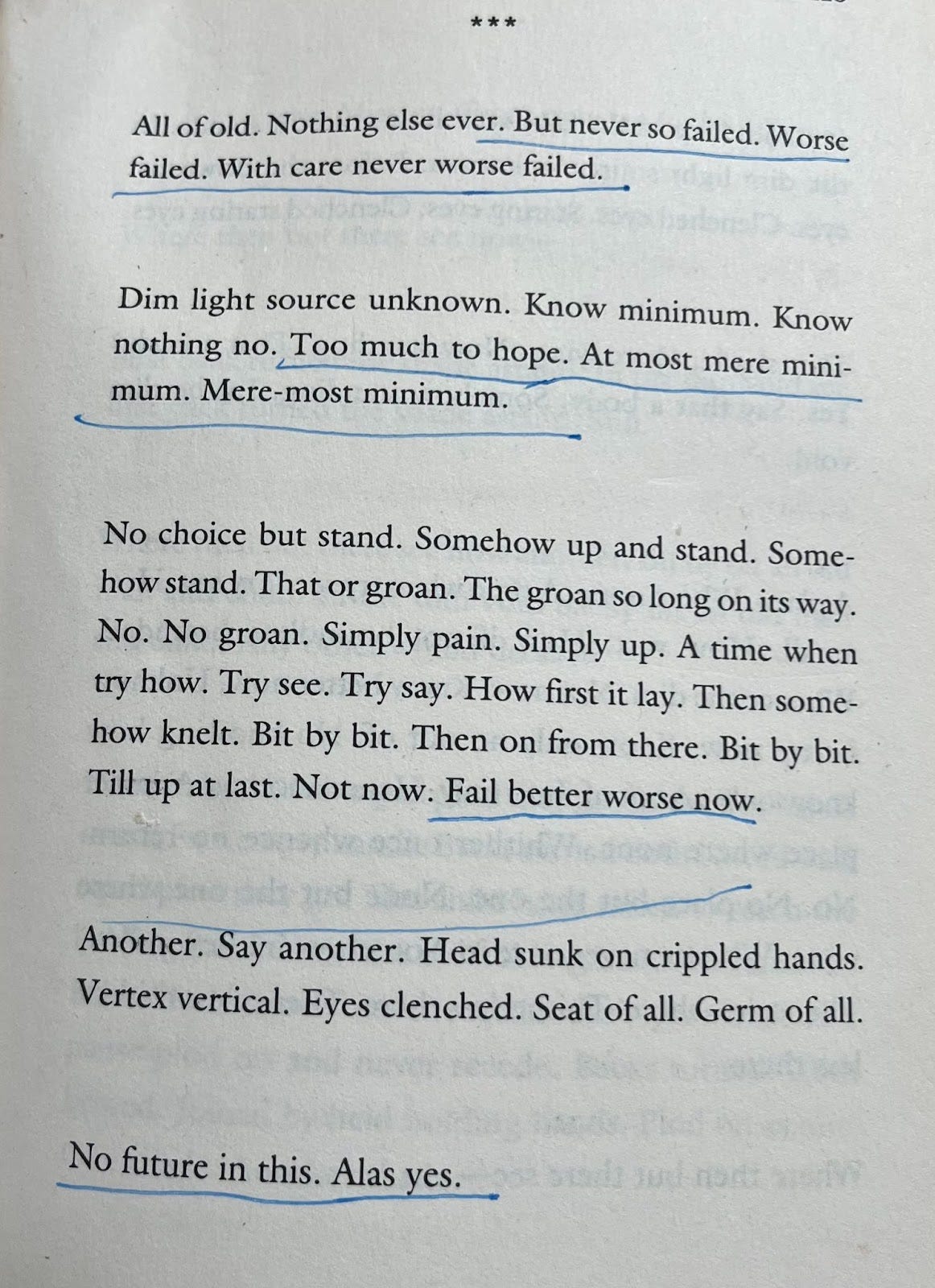

“Fail better worse now.” That’s how I read it in my head, with every word emphasized; each word its own crystallized meaning and also crucial to the larger sentiment. The magic trick in the Beckettian sentence is how abstraction structures coherence and vice versa. In other words: The words both mean more and less than what they say. A lot of nothing. This is to say that maybe “nothing” is, ultimately, “too much.”

“Fail better” on its own might convey that an individual, though failing, is, over time, improving in their attempt to complete the task they set out to accomplish. They’re getting closer to their goal. “Fail better worse,” however, indicates that your better is worse than what you could ever imagine. Maybe doing better will be your undoing.

Think of it in relation to Amelia Bedelia. When Amelia did the thing she was supposed to do wrong the effect wasn’t that she did the wrong thing, but actually that she made a new thing altogether. If Amelia were to fail, but fail better, that would simply mean she would do a mediocre job of an ordinary household task for her employer, rather than what she does instead, which is hilarious.

The Beckett quote is about failure as a thing that gets worse for the one who fails. It’s about how failure is a thing that deepens, a thing fathomless, a thing infinite in its trajectory. I keep calling failure a “thing” because I want to emphasize its complicated status as an action—like language, it’s something you do—but also a force—of nature, or something else, depending on your belief system. In other words: We do failure, but failure also fucks with us. It makes us and takes from us, sooner or later.

I’m by no means the first to write about this particular Beckett quote as a cultural phenomenon. I know I’m not just late, but very late to this particularly irritating party. On January 29 in 2014 Slate published a piece by Mark O’Connell about the quote’s ubiquity. The article documents the rise of the quote as a mantra for start-up culture, specifically in Silicon Valley. O’Connell cites an article for The New Inquiry by Ned Beauman from February 9, 2012. I found the New Inquiry piece before I read the Slate one, and felt less alone when I noticed that both O’Connell and myself singled out this insight from Beauman, a novelist:

Watching a liturgy from such a gloomy and merciless author getting repurposed to cheer up mid-level executives is like watching a neighbour clear out their gutters with a stick they found in the garden, not realizing the stick is in fact a human shinbone.

But it’s what he says after this that really gets at the meatless gristle of Beckett’s preoccupation with failure as communication’s ontic1 condition:

When Beckett talks about failure, he's often talking about how language can't withstand the weight of the meaning you want to put into it, and in that sense his unintended ubiquity is ideal: What better argument for the feebleness of determinate meaning than the tawdry afterlife of “fail better”?

I do think that Beckett would think it was funny the way the quote has metastasized. And, honestly, that gives me comfort. The reason I felt compelled to write this piece in the first place—despite the fact that the quote’s ubiquity and the ramifications thereof have been thoroughly covered—is that I don’t think even Beauman gets at why exactly this whole thing fucking sucks so much.

It makes me sad. As a graduate student, I had a professor who LOVED the quote, and used it to instill in us the importance of “shitty first drafts.” And I do believe in shitty first drafts! I do believe that writing a shitty first thing is essential to writing something that isn’t as shitty in the future! I just don’t think any of that has anything to do with failure. If “failure” is merely a vibe—a name for not feeling good about yourself, like when you write a shitty first draft—but this vibe still maintains its status as a mode of abjection, then I think that understanding offers a much bleaker view of humanity than I think even Beckett imagined. And that makes me feel very lonely, lonelier than anything Beckett intended for his reader to experience. I really believe that.

And I’m not saying that Beckett’s intention especially matters. I’m identifying what I think the quote means by reading it closely, thinking about how the words work semantically, i.e. in relation to one another. That close reading is guided by my knowledge of Beckett’s work more generally, sure, but, as O’Connell notes, Worstward Ho! is “one of the most tersely oblique things Beckett ever wrote.” It’s a variation on a theme, but singularly so. More same. Same no more.

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter.” What if when Beckett writes “no matter” he means that there is “no matter” ? There’s nothing, there. Here.

Thank you for reading.

I looked up “ontic” to make sure I was using it correctly and learned that there is also a software company named “Ontic.” They are a security software company and their product is a “Protective Intelligence Platform.” When you open their site, the first thing you see is this statement: “Let’s make nothing happen together.” I am not kidding.

"Dim light source unknown...The groan so long on its way."

I love it. Accidental poetry, intentional poetry, incidental poetry? Who cares!