Hello, everyone! Today’s post is about Amelia Bedelia. In the first post of this newsletter, I talked about Outside Bones as an opportunity to think associatively and to get weird. I think this post does that. I hope you like it. Special thanks to Graham Carlson for keeping my head on straight.

I never know how to start things. Endings are better because endings are more intuitive. Often, things just end. Things never just start. There has to be, even in gesture, some act of creation in the rendering of a start. There must be intent, an exertion of some will or impulse—even if that will or impulse, sometimes, exceeds our grasp.

In humanities scholarship, when we start something, we are taught to set the scene. Often, we deploy a pithy anecdote exemplifying the thing we are about to discuss. “Thursday, February 25, 1830 seemed like any other day—or any other day in the early part of Pisces season, anyway. But Théophine Gautier, as he strolled through the doors of the Comédie-Française in Paris, knew that tonight would be no ordinary evening at the theatre.”

You set the scene, and then you make your argument. “The clamorous fury incited by that evening’s production of Hernani by playwright Victor Hugo finally brought Romanticism to France. In this essay, I argue that the reaction to Herani’s premiere prefigures the riotous tumult that occurred upon the premiere of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi on December 10, 1896. As such, the two premieres, in a dialectic, stage the essential primordial drama between the Romantic Pisces and the analytic Sagittarius.”1

Sometimes I think about how many insanely popular plays and songs and revues there were in the past and how no one even thinks about them now. When Hernani premiered, the audiences freaked out so much that you couldn't hear the actors’ lines from all the shouting. They were so upset because the play transgressed the lines of neoclassicism. Hugo used the play to further the tenets of Romanticism, which at that time was, as an impulse or trend, still in its infancy in France.2

It’s weird to think of Romanticism as a kind of avant-garde, but it kind of was. Think of it like a Jeff Foxworthy joke:

“If YOUR PLAY….violates the ARISTOTELIAN UNITIES of ACTION? TIME?? AND PLACE???………your play might be avant-garde.”

“If YOUR PLAY…… ‘is half lamentation, half lampoon; half an echo of the past, half menace of the future; at times, by its bitter, witty and incisive criticism, striking the bourgeoisie to the very heart’s core; but always ludicrous in its effect, through total incapacity to comprehend the march of modern history?’.....your play might be avant-garde.”3

Romanticism is a rupture, it exposes. Romantic irony, chiefly, is

A kind of literary self‐consciousness in which an author signals his or her freedom from the limits of a given work by puncturing its fictional illusion and exposing its process of composition as a matter of authorial whim. This is often a kind of protective self‐mockery involving a playful attitude towards the conventions of the (normally narrative) genre. (link)

Like Romanticism, transgressive art—specifically the avant-garde of the mid-twentieth century—involves a playful didacticism. The interest in rupture persists; to perforate, to puncture, to explode—these are avant-garde imperatives.

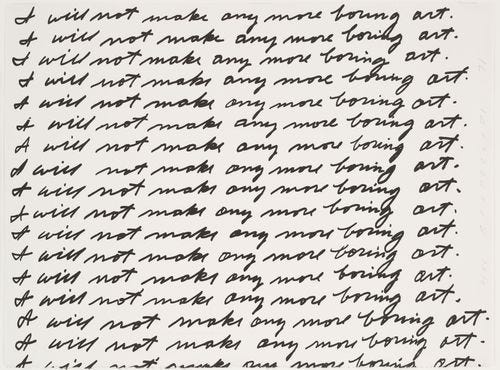

In particular, I think Fluxus shares a Romantic spirit: the desire to abstract, to abnegate, to use the aesthetic tactics of desire to touch nothing. At the very least, the Fluxists knew what they didn’t want. Look at John Baldessari’s “I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art” (1971):

(link)

The period at the end of every line, the ink blot dot to end the thought. Careful scribble, a reminder, what to do next, dot. The dot is the promise, the X marks the spot for the unknown next thing. We know what we are not making. We have a hunk of clay, and we are making a sculpture of the future, but it can’t have anything in it from today, including the clay.

Yoko Ono had Baldessari’s trouble, too, but with textiles, including her skin. In Cut Piece (1964), she invites the audience to help her figure out what her cloth blot dot will be. Interestingly, even though the piece is so granular, textile-tactile, when she describes the work, Ono talks about it sonically:

When I do the Cut Piece, I get into a trance, and so I don’t feel too frightened….We usually give something with a purpose…but I wanted to see what they would take….There was a long silence between one person coming up and the next person coming up. And I said it’s fantastic, beautiful music, you know? Ba-ba-ba-ba, cut! Ba-ba-ba-ba, cut! Beautiful poetry actually. (link)

So the dot is the cut. The cut is a movement, a choice, a rupture. Ba-ba-ba-ba, cut! Rup-rup-rup-rup! ‘Ture?

I’m not sure. The thing connecting whatever the hell it was Hugo wanted and what Baldessari and Ono wanted seems like a kind of flooding. Fluxus was all about the flood. Flooding of categories, sure, like aesthetic conditions and fabrics and words and images and things, but also the flooding of aesthetics with emotions. The entanglement. Maybe what made everybody so mad at the Hernani premier is the same thing that still, to this fucking day, in the year of our Lord 2022, makes people so mad at Yoko Ono. What is this, a cut piece or a sound piece? If we cut her clothes, what’s next? You’re telling me a cut made this piece?

I’m not saying that what makes Ono make art is, like, in a direct relationship to Hugo’s Romanticism, like you could draw a straight line from that night in Paris in 1830 to 1964. I’m not even trying to say that Ono and Baldessari have anything in common beyond the Fluxus affiliation, a shared value in knowing what they don’t want. The thing about Fluxus in the first place is that everyone involved is kind of doing their own thing. If it is a community, it’s a community united by a shared disavowal, a shared tiredness and disinterest in the clay of today. Fluxus is a community grounded in mutual dissatisfaction.

Here’s Yoko One screaming about it:

I guess I’m just interested in whatever the methods are that artists use to portray, suffer, or work against this dissatisfaction. And I guess, for the purposes of this piece, I’m interested in calling whatever those methods are—in whatever form or disjoint, scream, cloth, dot, or cut—the avant-garde. The avant-garde, as an impulse, is composed of two imperatives: to expose and to critique. It is my life’s work to show how this impulse plays out across genres, disciplines, and aesthetic frameworks. The avant-garde is more of a drive than a category. The avant-garde drives categories. The avant-garde drives categories off the road and into beautiful and fucked up ditches.

The avant-garde drive, the avant-garde dérive. When Yoko Ono screams against the sky, she’s deploying the materials at hand—the sonic textures and tones that make up her voice—and wielding them toward the materials of the world: the wind, the wall, the sky. The mixture is the exposure; how are screams always already a kind of wind?

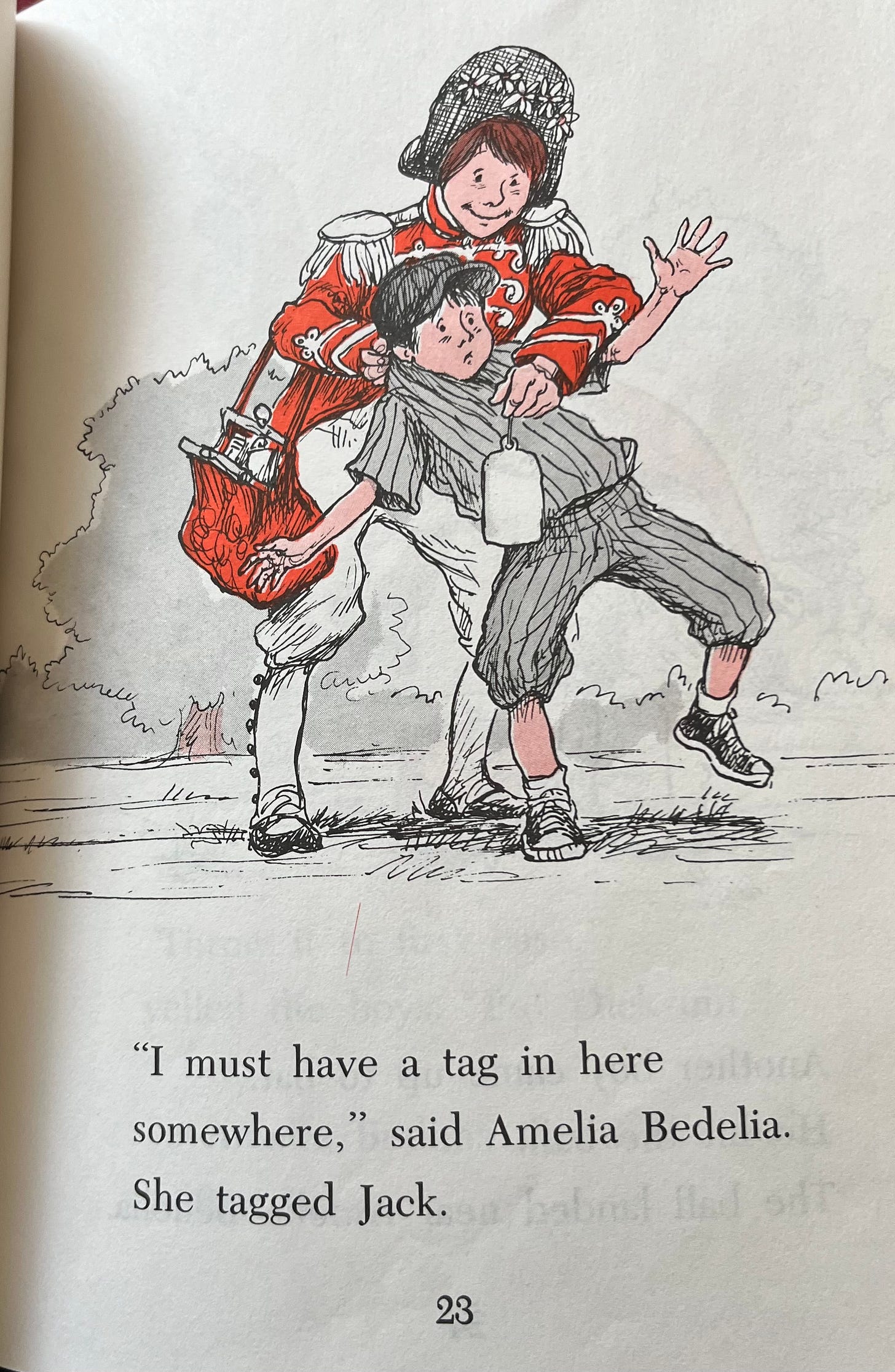

In Amelia Bedelia (1963),4 the famous maid of children’s literature arrives at her job on her first day only to catch her new bosses as they are on their way out. “‘But I made a list for you. You do just what the list says,’ said Mrs. Rogers.”

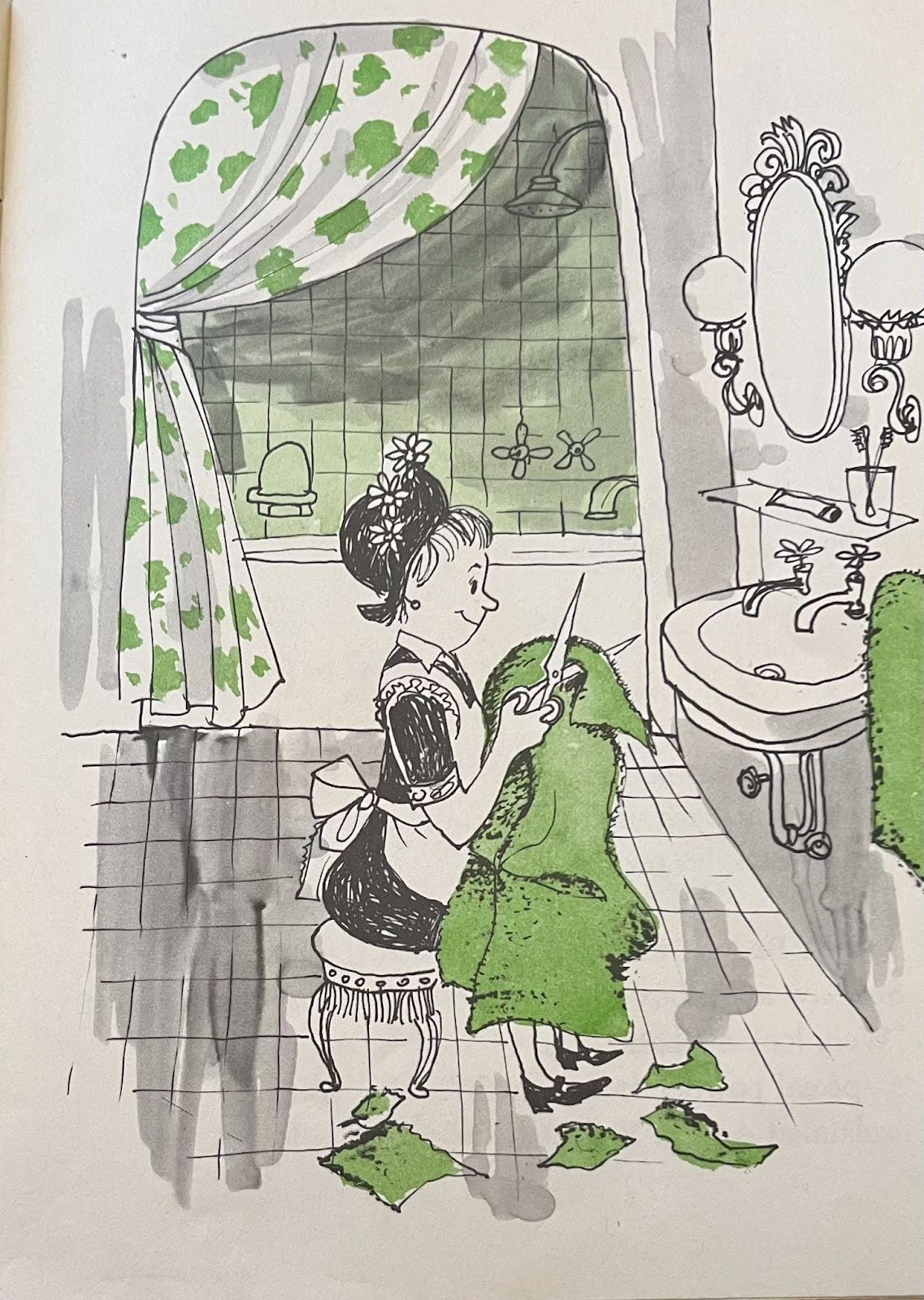

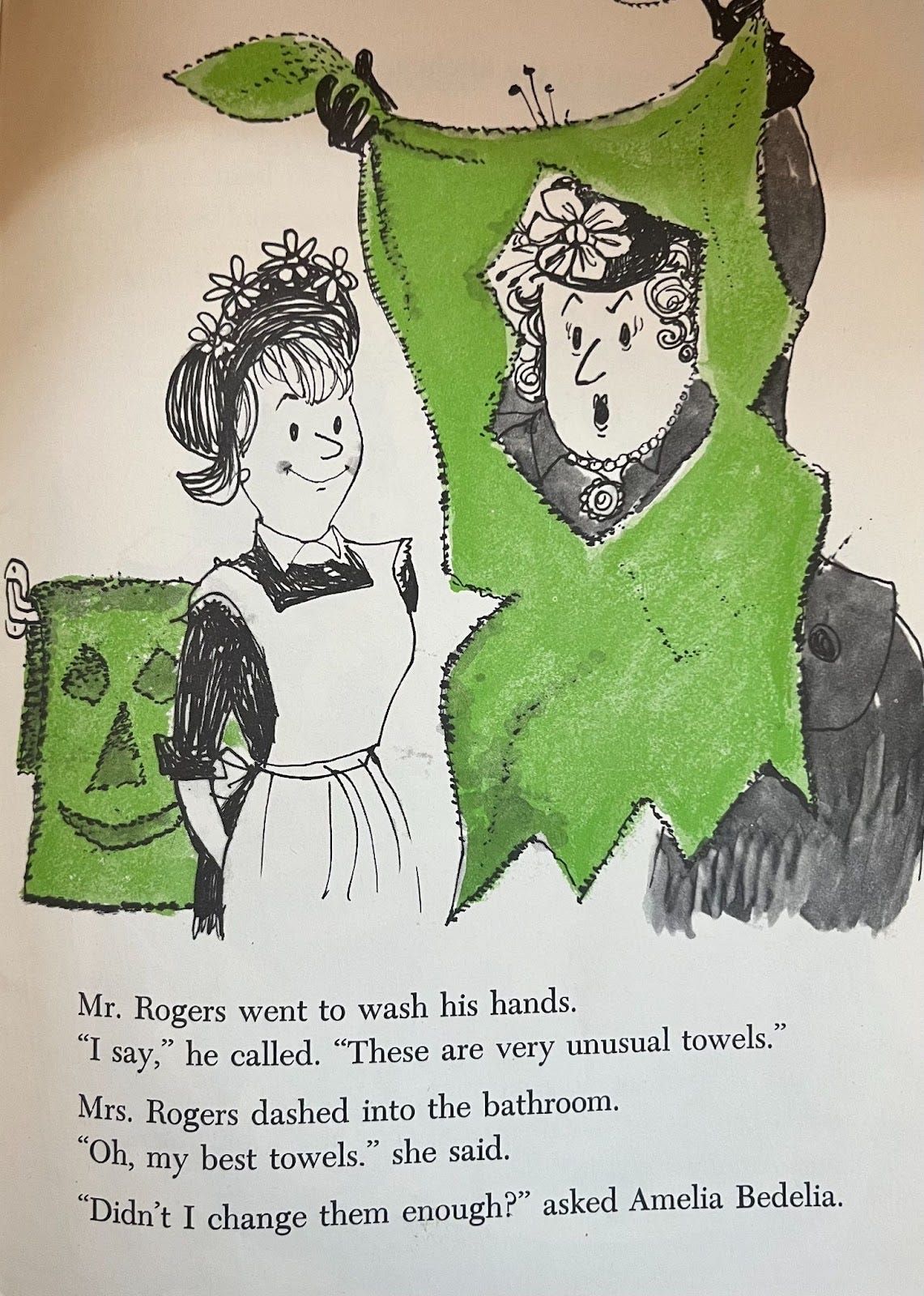

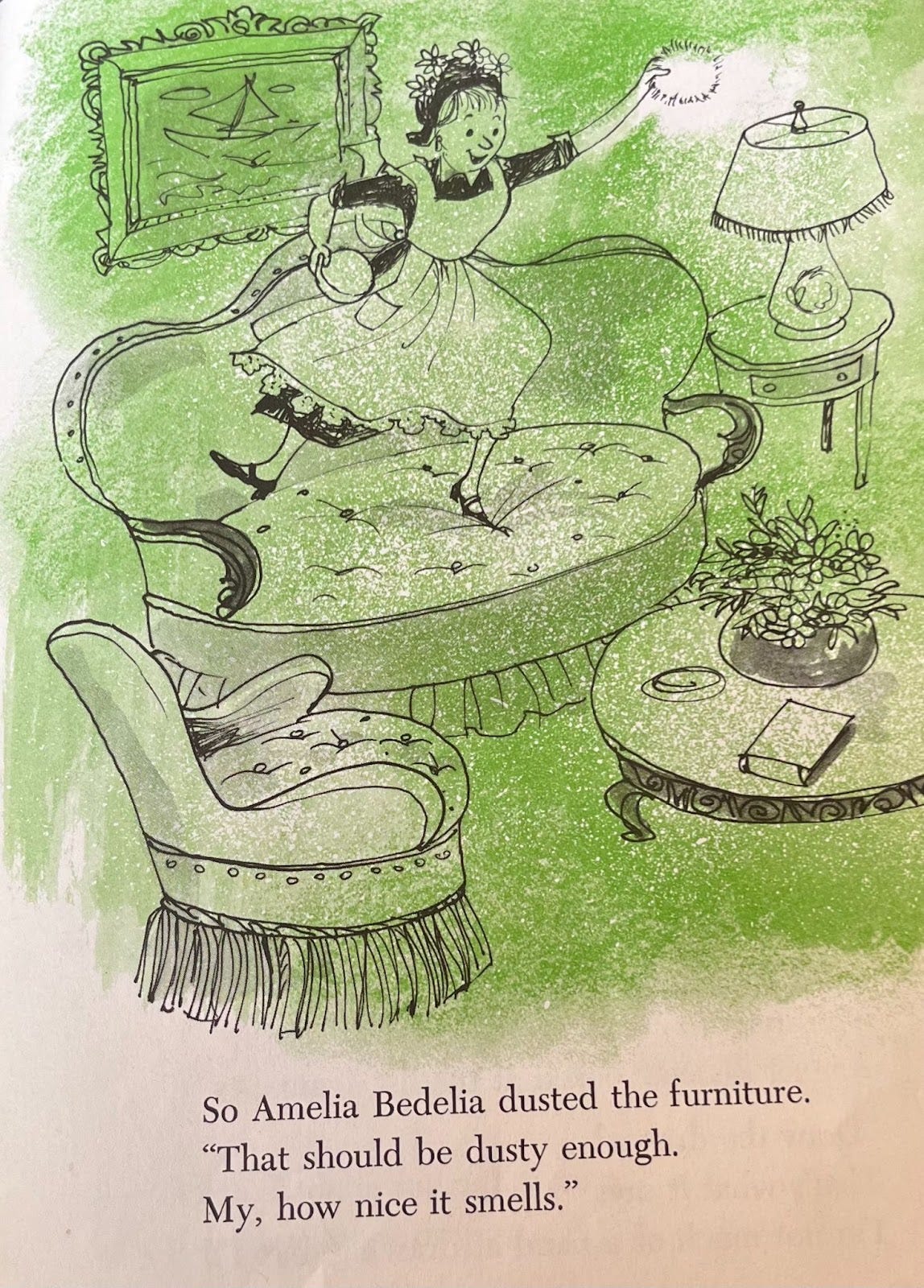

So Amelia Bedelia looks at the list, and follows it. She changes the towels in the green bathroom. She dusts the furniture.

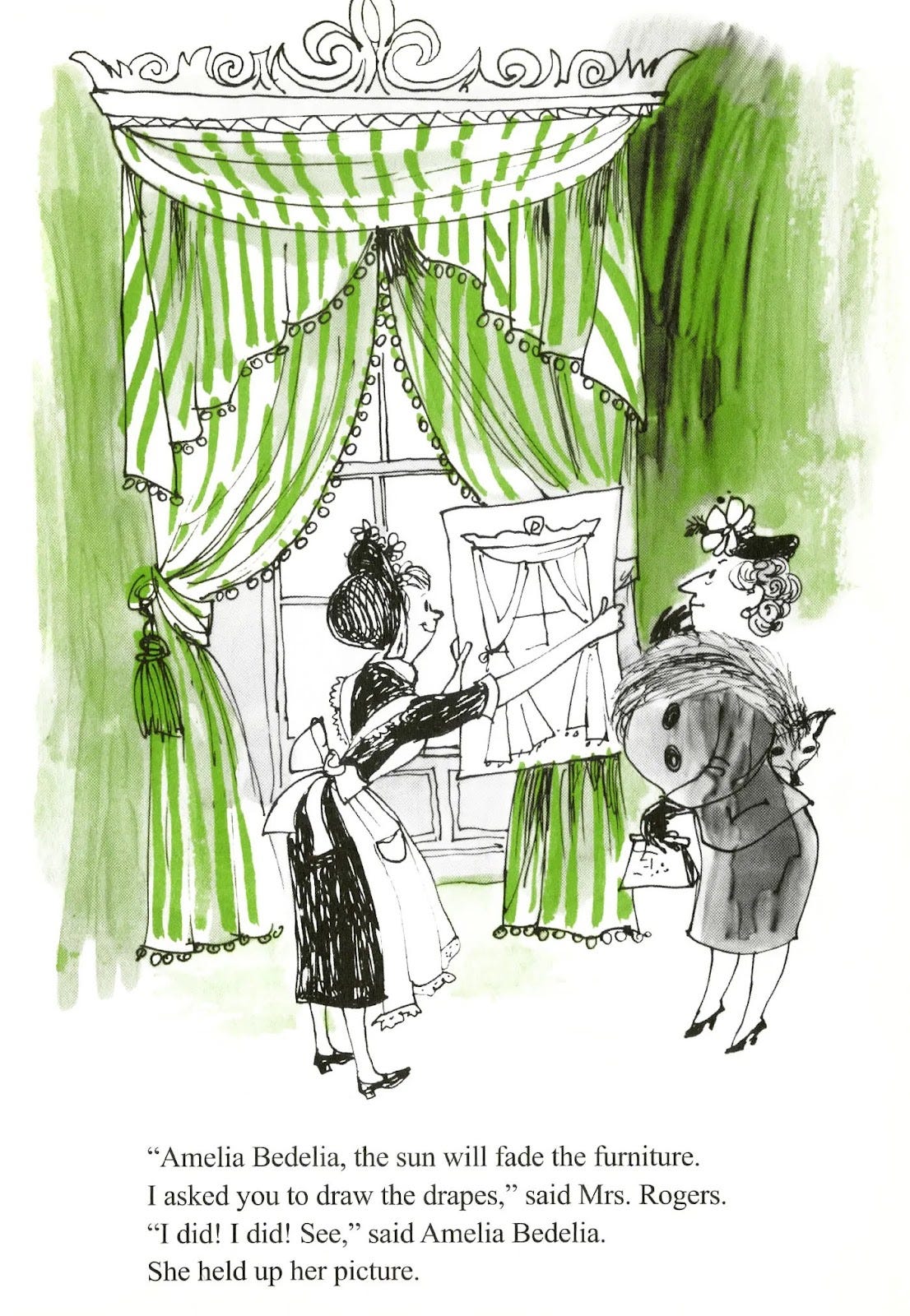

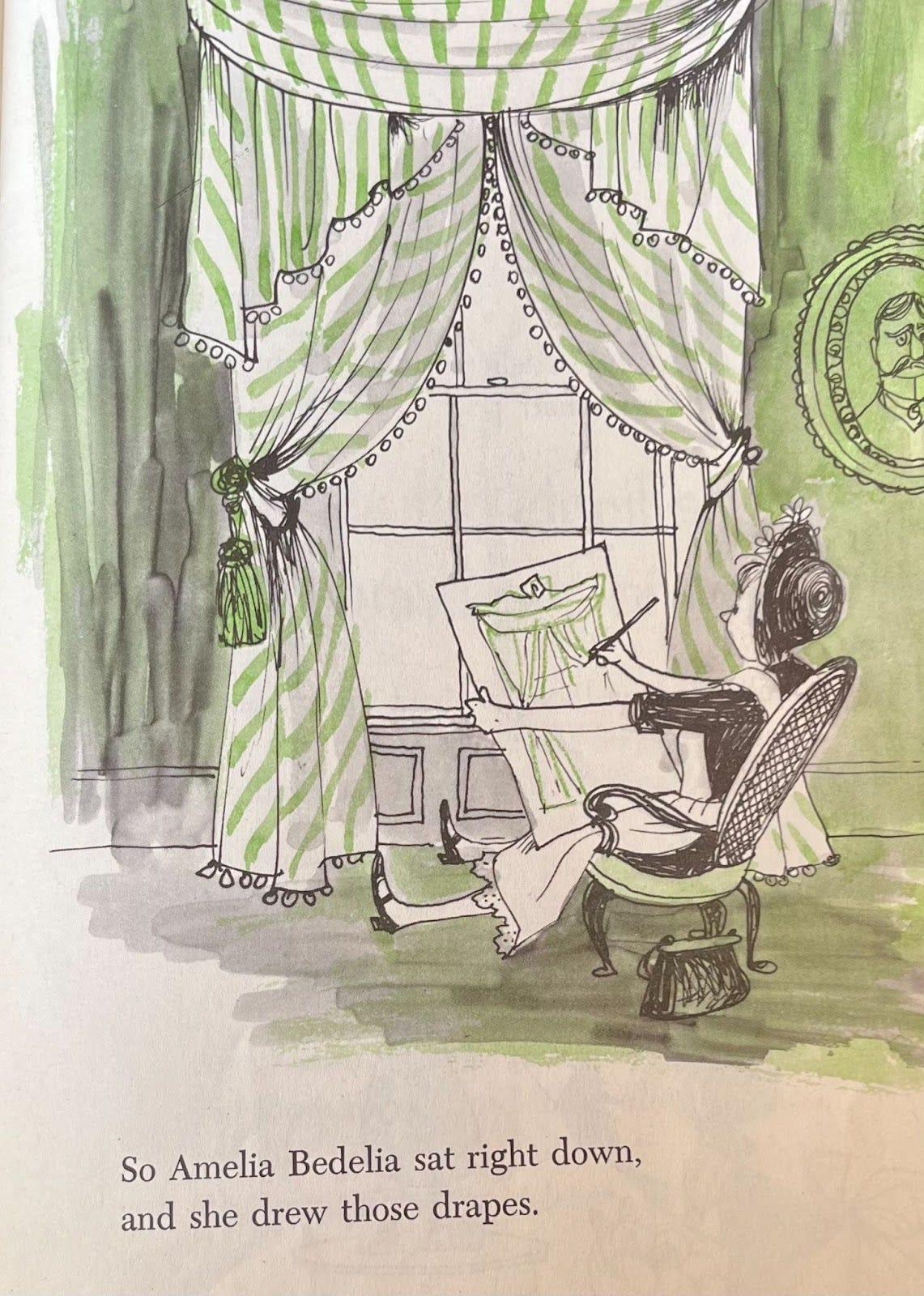

Amelia Bedelia draws the drapes.

According to Sarah Blackwood for The New Yorker, Amelia Bedelia is a twist on the conventional household (white)5 maid archetype that is a hallmark of children’s literature. She writes,

Each book follows a simple formula: Amelia Bedelia, a housemaid replete with apron and frilled cap, encounters various domestic imperatives: clean the house, host a party, babysit, substitute-teach. But, rather than keeping order, Amelia Bedelia creates disarray. She takes each instruction she is given with an absurd literalism.” (link)

Because of Amelia’s literalism, she has been taken up by some as a neurodivergent icon. Janae Elisabeth, writing as Trauma Geek, ties Amelia’s literalism to the sense of directness that is characteristic of how people with autism communicate. That directness, she notes, can have a comic valence; it “lends itself to a particular kind of humor that disrupts the default understanding of a word or concept.” (link)

When Amelia draws the drapes, she makes evident that her boss’s meaning of “draw” is an appliqué, a construct, an implication. “Draw” in its most immediate or literal definition is, clearly, the artistic practice of drawing, of making lines into images. To “draw” per Mrs. Rogers’ sense of the term is secondary to this essential urge. In this way, what Amelia exposes is the multivalency of language, the ever-shifting capacities for control that language affords the powerful and deprives from the powerless. When Mrs. Rogers returns and Amelia Bedelia shows her the work that she’s done, Mrs. Rogers—I imagine, in my adult wilfully imaginative reading, in the far more transparent politics my mind bestows—realizes that (Amelia’s) “work” does not necessarily equate to her own understanding of “success” or “completion” or “competence.”

As Blackwood writes,

[Amelia] dirties and destroys her employers’ possessions, in other words, breaking one of the primary taboos of domestic employment. She’s a figure of rebellion: against the work that women do in the home, against the work that lower-class women do for upper-class women.

This is to say: Amelia Bedelia, armed with neurodivergent literalism, does something similar to Ono’s “Voice Piece for Soprano.” Ono—remixing voice and/with/as wind. But Amelia, well-meaning as she is, ultimately, through her interpretive action, is “against the work.” Wind/work.

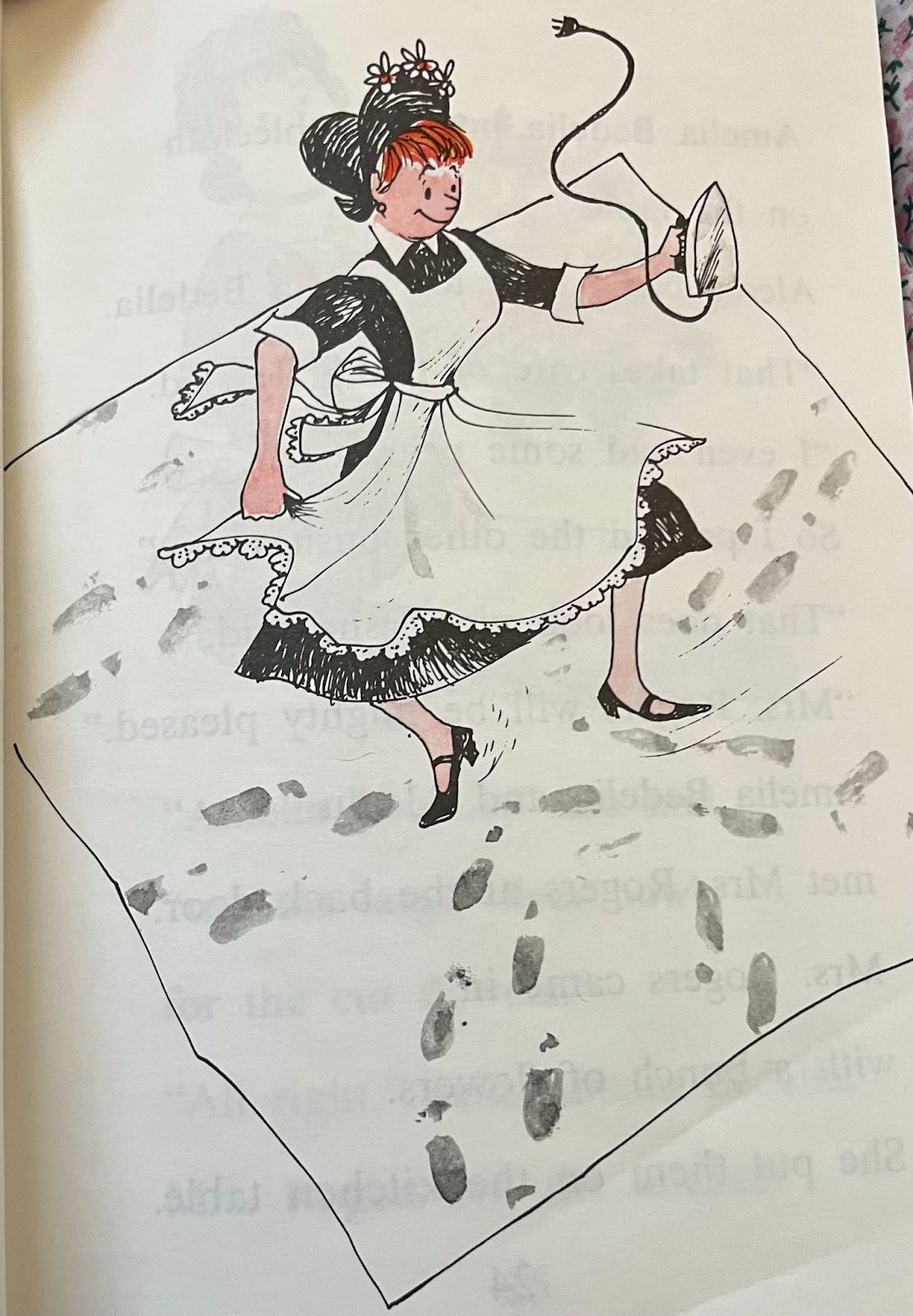

In Amelia Bedelia and the Surprise Shower,6 Amelia is asked to “run over” a tablecloth with an iron. She picks up the iron, and runs all over the tablecloth in her high-heeled shoes. It’s a kind of dance, but also a painting.

Thinking with the avant-garde, I want to take seriously the internet people’s hailing of Amelia as a neurodivergent and disability icon. If Amelia makes a painting like the Gutai Group, then her painting takes on the aesthetic materials of the Gutai group and recasts them in light of her disabled iconicity, per her internet admirers. Maybe this is…disability aesthetics?

According to Tobin Siebers,

[D]isability aesthetics embraces beauty that seems by traditional standards to be broken, and yet it is not less beautiful, but more so, as a result. Note that it is not a matter of representing the exclusion of disability from aesthetic history, since no such exclusion has taken place, but of making the influence of disability obvious. This goal may take two forms: (1) to establish disability as a critical framework that questions the presuppositions underlying definitions of aesthetic production and appreciation; (2) to elaborate disability as an aesthetic value in itself worthy of future development.

My claim is that the acceptance of disability enriches and complicates notions of the aesthetic, while the rejection of disability limits definitions of artistic ideas and objects.8

This is not to say that disabilities—specifically, for us, learning disabilities— are metaphors for transgressive art. Rather, learning disabilities as frames of reference offer the tactics for transgressive performance. Thinking speed-as-episteme (Amelia thinks and works so fast) and thinking textiles as conducers of sonic experience (like Ono’s interpretation of Cut Piece), I believe, is a deconstructive process. These frames offer new ways of thinking and feeling by the exposure of the status quo as a construct imposed by those in power. Is that not the avant-garde?

Disability aesthetics, Fluxus, wind/work—all this aridity is, of course, my adult fanciful version of close reading, my stubborn abstracting of Amelia’s “yes, but”-ing the orders she is given. It’s not too weird that I do this, though; children’s literature like the Amelia Bedelia books invite this line of thought because children’s book writers are interested in appealing to the sensorial minds of children, the vagaries of literal thinking, and humor. These are precisely the kind of interests that certain overeducated adults and nostalgic weirdos (but I repeat myself) are similarly invested. As Blackwood points out,

[m]any classic children’s books beg for philosophical readings: the likes of Charlotte’s Web or Are You My Mother? are well known as complex and subterranean ruminations on death and identity and community.

All this aridity is very different from the kind of experience I had when I read the Amelia books with my dad as a child. Then, I wasn’t thinking at all about such things like labor’s ontology, or the relationship between art and art’s making, of what art can do. For his part, my dad would groan at Amelia’s haplessness, cringe-react to her abstraction.

For me, I was thinking and experiencing it more on the level of sensation. But still, like Yoko, maybe, with the Ba-ba-ba-ba, cut! Textures mapping onto sensations, lateral, literal. Feeling what Amelia is doing, feeling myself differently. Maybe doing things wrong isn’t always the wrong thing to do.

It’s important to note that Amelia is a multidisciplinary artist. She likes to mix mediums. That said, she is famous for her culinary arts. Indeed, when I read the books as I kid, I loved looking at all the things Amelia cooked and baked, and really wanted to eat them.

Of course, children’s literature is chockfull of delicious things. Or, at the very least, things that seem delicious. The British are especially good at conjuring delicacies. C.S. Lewis in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe: Edmund and his Turkish Delight along with whatever was in that tea Jadis makes; also the fish the otters catch and prepare for the Pevensie children.

Another point for the British: Lewis Carrol and Alice’s “eat me” cake and mushroom, along with the oysters that the walrus and the carpenter enjoy. I think the British, like children, enjoy coziness, and food is one of those things that is vital to this ambience. Amelia Bedelia, though an American, is a maid: her job is to create ambience, especially a cozy one. So she bakes, and her wards eat. It’s all very cozy. It’s cute.

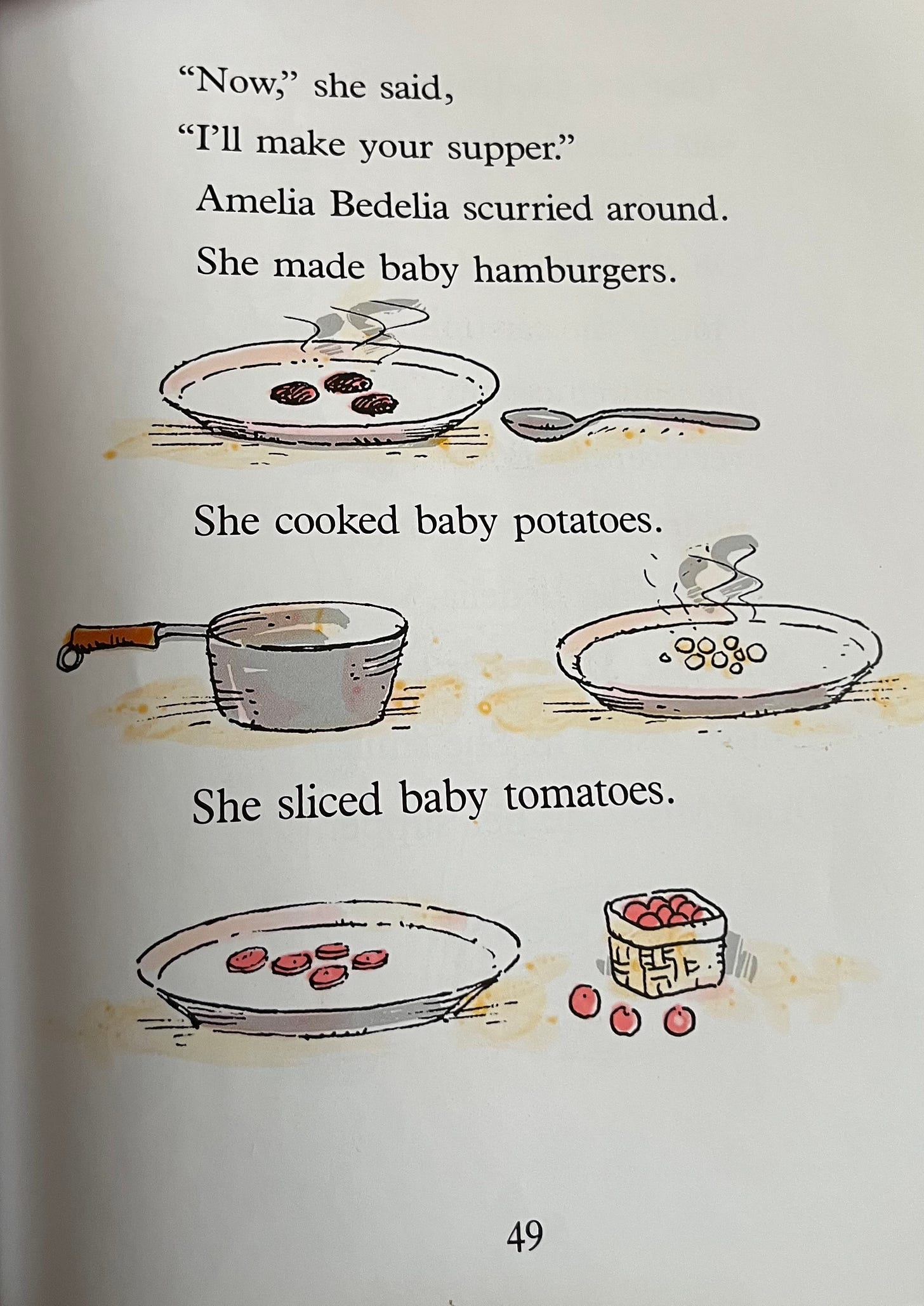

In Amelia Bedelia and the Baby,9 Amelia is instructed to prepare baby food for the baby. So she does.

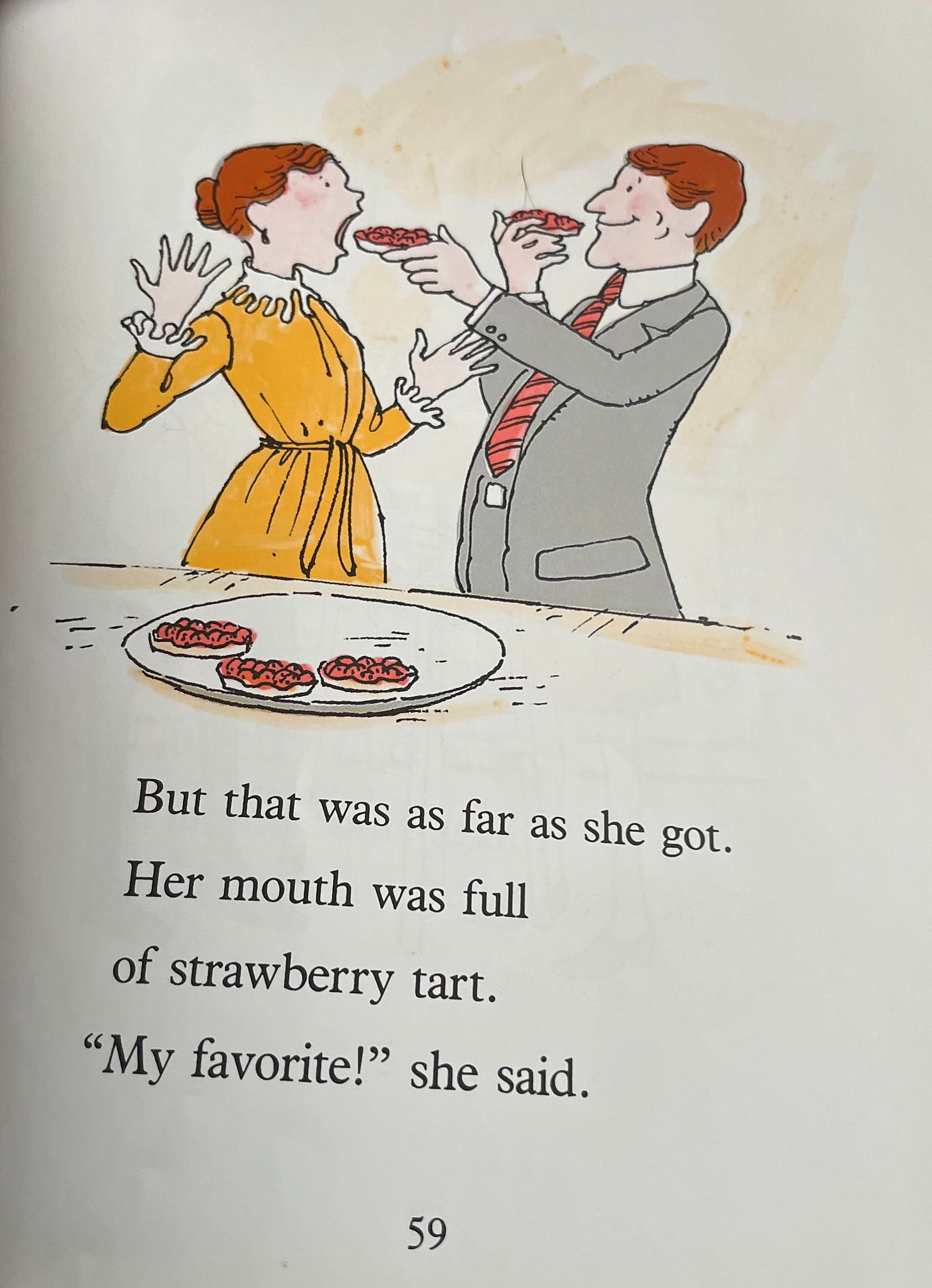

She also makes strawberry tarts. When the parents come home, they are so delighted by the strawberry tarts that the dad even feeds one to the mom. Cute. Kinda gross, though, too.

Similar to their role in children’s books, the aesthetics of consumption are also integral to the avant-garde. What’s more, according to Sianne Ngai, is that, by the same coin, the avant-garde is also invested in cuteness. Cuteness as an aesthetic mode registers, prominently, in the act of (self-)commodification. Both cuteness and the avant-garde are inherently concerned with power. Specifically, cute things and the avant-garde register the role of powerlessness in the experience of commodification. Ngai writes,

For it is not just that cuteness is an aesthetic oriented toward commodities. As Walter Benjamin implies, something about the commodity form itself already seems permeated by its sentimentality: “If the soul of the commodity which Marx occasionally mentions in jest existed, it would be the most empathetic ever encountered in the realm of souls, for it would have to see in everyone the buyer in whose hand and house it wants to nestle.”10

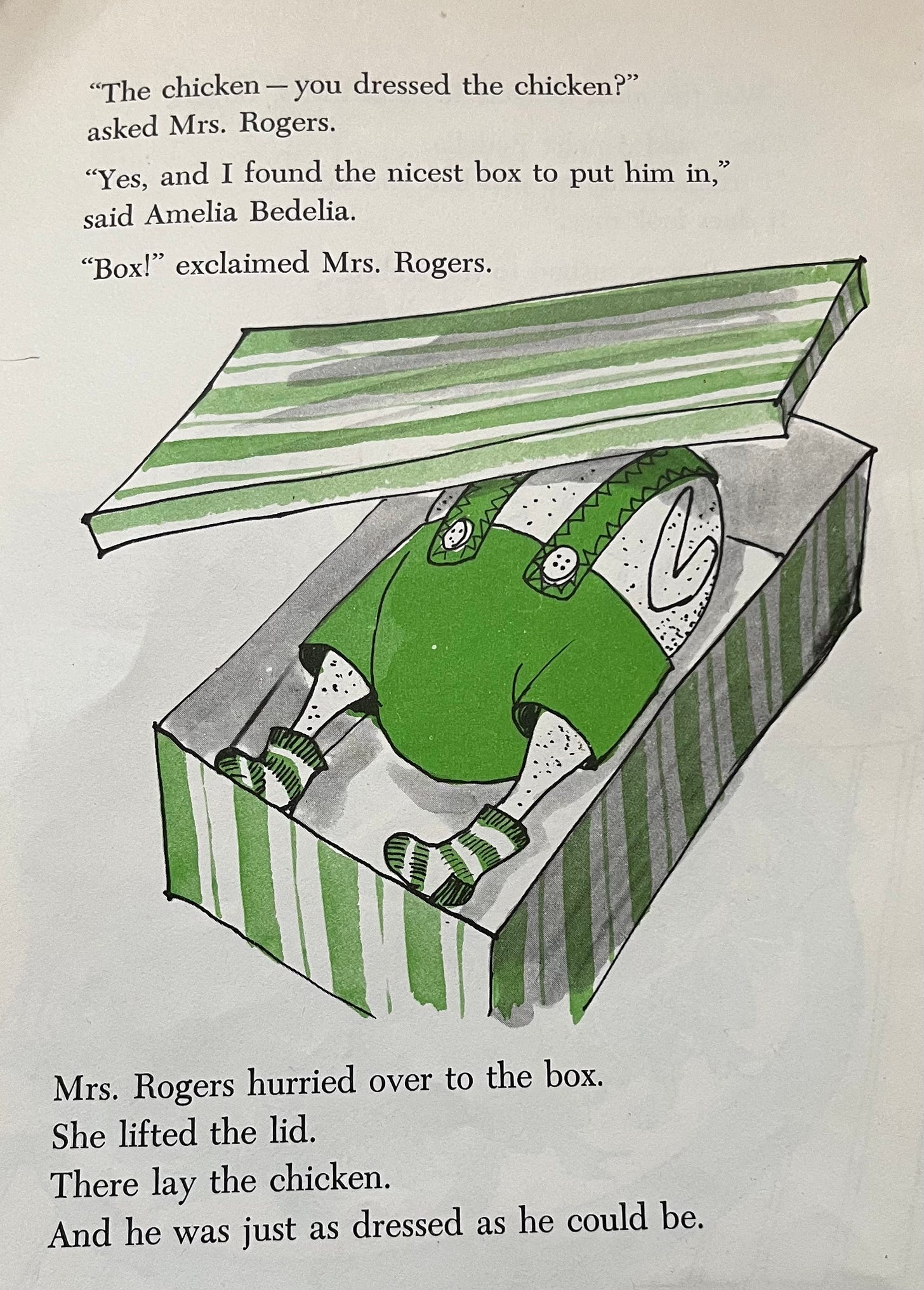

Look at this dressed chicken, nesting in a lovely green box. This is from the first book, the same one as the curtains. Look at the chicken’s little green socks.

Here we see the mixing of the materials of humanity with the materiality of the animal, specifically the dead and edible animal. Looking, I’m reminded of a less cute version of this kind of mixing, though one that shares an interest in intimacy through consumption—perhaps an intimacy maybe adjacent to the kind shared by the feeding parents in Amelia Bedelia and the Baby.

Here’s an image from Meat Joy (Carolee Schneemann, 1964):

(link)

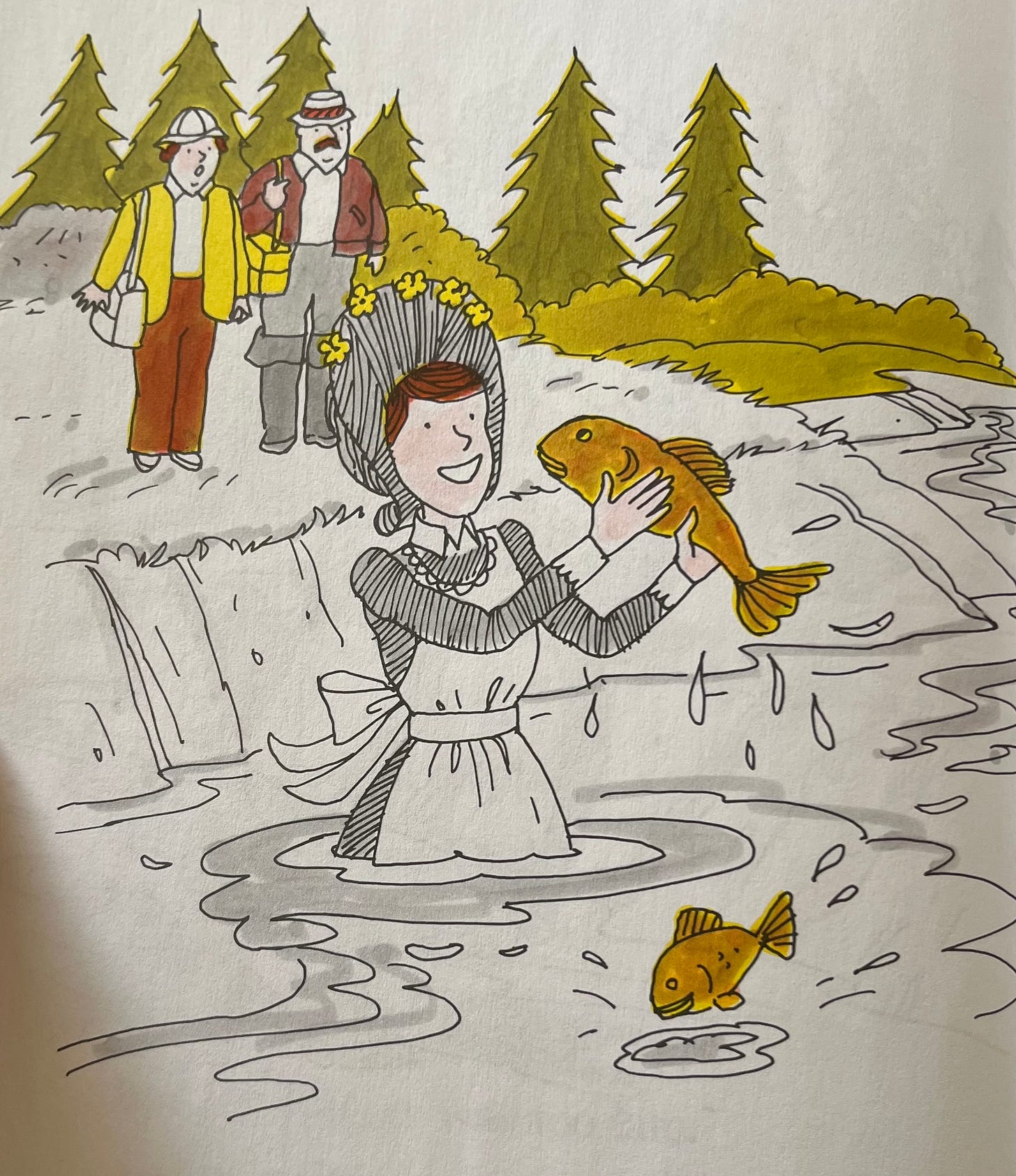

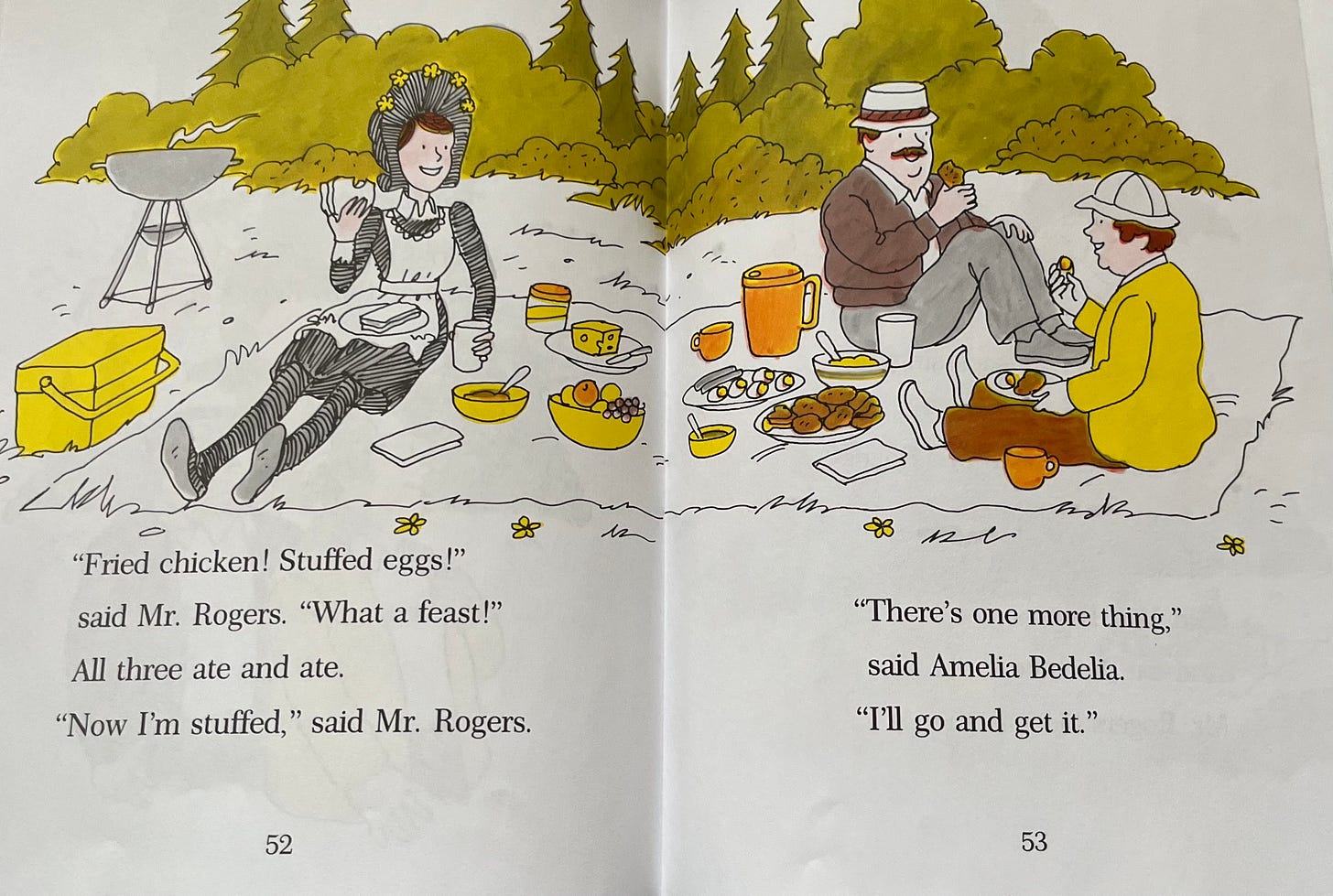

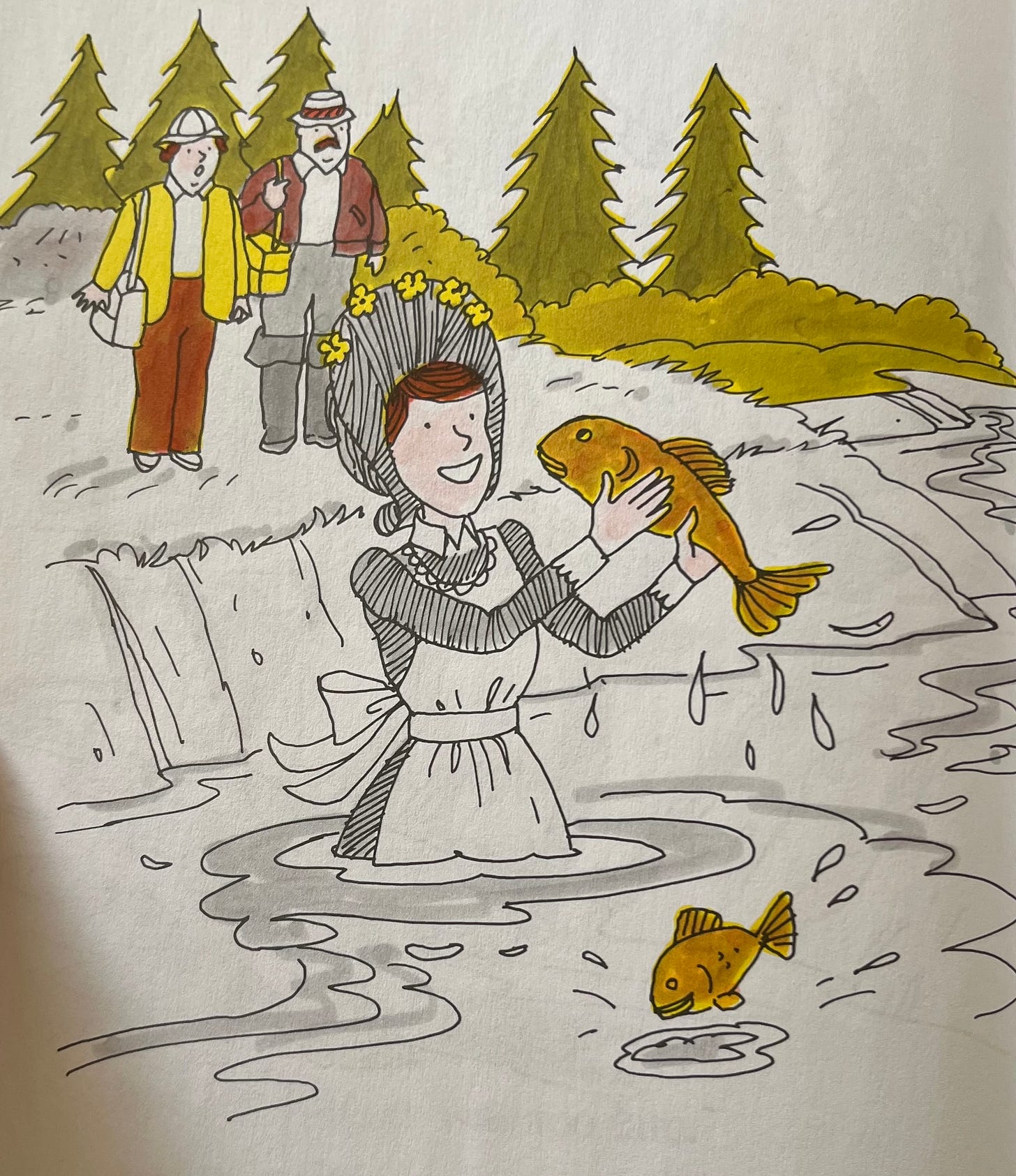

By the end of Amelia Bedelia Goes Camping,11 a more wholesome picnic takes place.

It’s not that I think Meat Joy is exemplary of disability aesthetics. I don’t think that at all.12 I’m not sure the chicken with the socks and lederhosen is exemplary of disability aesthetics per se either; I mean, it only really is if art historians agree with me (and the other internet people) that Amelia Bedelia is a neurodivergent icon.

I’m just saying it’s kind of weird how much canonically avant-garde art links up with the themes and aesthetic investments of a neurodivergent fictional character from children’s literature. What is the deal? Siebers recognizes disability as always already an aesthetic condition, and understands that aestheticism as a relationship to the world, not as a bracketing or limiting kind of objectification. Disability, when considered aesthetically, becomes a condition of possibility. I guess I like anything that wants to be something else. Currently, the world is fucking terrible. Follow Amelia’s lead. Misinterpret what your boss says and make something weird. Play baseball in a weird outfit.13

If I sound precious and twee, it’s because I am. Like I said, Outside Bones is my opportunity to get weird and ruminative. Sometimes rumination manifests as a kind of self-indulgent, cutesy listlessness. I’m without a list. I need a job like Amelia’s, maybe.

To end:

In Amelia Bedelia Goes Camping, Amelia catches a fish with her bare hands. She stares into the abyss (fish), and the abyss (fish), stares back at her.

As much as Amelia’s literalism might make us groan, we groan in recognition of a world viewed aslant. A total normie like Paul F. Tompkins may say: Death to Amelia Bedelia. But to him I say: Long Live Amelia Bedelia! Thank you for reading.

Whatever.

There are a bunch of reasons for why Romanticism was popular in Germany and England and Spain and not France in 1830. I would go into them, but they don’t really matter for the rest of this piece. And anyway, we are on the internet. If you’re curious, go on Wikipedia or the Stanford Encyclopedia or the Dark (Romantic) Web.

My husband André wrote these two: “If your play is FOUR HALVES of ANYTHING….it’s probably avant-garde!” “If your TV….is stacked on TOP OF ANOTHER TV….and that TV DOESN’T WORK…..your play might be avant-garde!”

Parrish, Peggy. Amelia Bedelia. Illustrated by Fritz Siebel. New York: Harper & Row, 1963.

I confess: there’s a ton of race stuff that needs unpacking here. It’s a weakness of the essay. I avow it. This isn’t an excuse, but an admission.

Parrish, Peggy. Amelia Bedelia and the Surprise Shower. Illustrated by Fritz Siebel. New York: HarperCollins, 1966.

For more on the Gutai Group, see: “Kee, Joan. “Situating a Singular Kind of ‘Action’: Early Gutai Paintings, 1954-1957.” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 26, no. 2 (2003), pp. 121-40.

Emphasis mine. That was a long block quote. I love block quotes. Anyway, see: Siebers, Tobin. Disability Aesthetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010, p. 3.

Parrish, Peggy. Amelia Bedelia and the Baby. Illustrated by Lynn Sweat. New York: HarperCollins, 1981.

Ngai, Sianne. Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015, p. 13.

Parris, Peggy. Amelia Bedelia Goes Camping. Illustrated by Lynn Sweat. New York: Greenwillow Books, 1985.

This isn’t really relevant, but I feel I must confess: I don’t particularly like Meat Joy.

Parrish, Peggy. Play Ball, Amelia Bedelia. Illustrated by Wallace Tripp. New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Completely flummoxed at the notion that the avant-garde is invested in cuteness! I can't think of one artist that would apply to. Gotta pickup Ngai's book I guess. Also, I feel like I'm on a similar wavelength as you and enjoyed this because I've been obsessed for the last couple months about how the avant-garde is inspired by the childlike and the immature but is overwhelmingly hostile to the actual child. Here too, I just imagine Yoko meangirling Amelia Bedelia so hard...